Nick and Helen Young are retracing the escape of his father, Leslie, from Fontanellato PoW camp, near Parma, after the Armistice with Italy on September 8th 1943. Their journey, undertaken in autumn 2017, is by car in three stages. As they travel south to Anzio, their final destination, they leave letters in the villages where Leslie hid, thanking the local people for sheltering him and risking retribution from the Germans and Fascists. Their journey is full of heart-warming and emotional incidents.

Day One

Seventy-four years and ten days after the 1943 Italian Armistice, I am in Fontanellato with my wife Helen, to follow my father’s 400-mile escape route from PG Camp 49 down to Anzio, just south of Rome. He went on foot – for us, it’s the car!

The prison camp, an imposing new orphanage before the war, is now a special clinic for neurological conditions, but it remains virtually unchanged, just on the eastern edge of town and overlooking open fields.

The area to the rear of the Camp, where the PoWs used to play football and exercise, is still surrounded by a wire fence – possibly even the same wire fence that nearly 600 prisoners marched through in columns of three all those years ago, immediately after the Armistice, saluting Colonel Hugo de Burgh (the senior British Officer) as they went! Rumour has it that Ronnie Noble took photos at the time – has anyone ever seen them? This was the yard that Toby Graham and others escaped from, having hidden themselves in a trench before the yard was cleared for the night by the guards.

We peer up at the facade, trying to see the bullet holes around the window of the famous bar – caused by sentries taking pot-shots at PoWs peeping out at the pretty girls passing by. We look for the window that Jack Comyn jumped out of, disguised as an Italian workman.

Then we visit the nearby Church of the Madonna of the Rosary: the nuns here used to do the prisoners’ laundry, and run little errands for them in the town. In the church, we pin up the first of many notices about my father’s escape that we intend to put up in every village he passed through. The notice, with a picture of my father, tells the story of his escape, says a little about the MSMT – and above all says a thank-you to the local people who helped him when he was ‘on the run’.

After lunch in a local cafe – great Parma ham and delicious ravioli – we set off for the dried-up stream bed, known as The Bund, near the hamlet of Paroletta, where the prisoners hid up after their escape, trying to work out which way to go. My father got himself kitted out as an unlikely-looking 6 foot Italian here, and set off just before dawn four days later with an RAF pilot called Reg Dickinson, heading south-west.

We finished Day One making for Dad’s first overnight stop, at Banzola, about fourteen miles from Fontanellato, in the foothills of the Apennines. One moment, we were in the flat plain, wondering how 600 men could have hidden themselves in the blank open countryside. Minutes later, we were suddenly in the hills, deeply-wooded slopes or precipitous fields rising steeply on either side of the road.

It was raining by now, and the September air was cool, the countryside lush and green. Many of the fields have been roughly ploughed already; in others, the dried brown stalks of the picked maize await their turn for the plough. The vines are heavy with grapes. Farmhouses show few signs of modernisation – some indeed are clearly deserted. It all looks much as it must have done seventy-four years ago.

We stop in a clearing, looking back towards the church in tiny Banzola. To our left is the hillside down which my father must have stumbled, dog-tired at the end of his first long day of real freedom. The village is quite silent and still in the late afternoon. We whisper quietly about what it must have been like, that first night as they tried to decide which door to knock on …..

DAY TWO

It was pouring with rain as we set off to drive the fifteen miles from Banzola to Vianino, along narrow roads swooping up and down the rolling rural hillsides at the start of the Apennine chain. With stops for photos and to check the map, it felt as if we had been driving for hours by the time we arrived at our destination. It must have been a completely exhausting walk for the escapers who set off from Banzola by moonlight at 3am and didn’t arrive in Vianino until the late evening. The village, with its tall rather gaunt shuttered houses, and its memorial to a Nazi massacre of local partisans in July 1944, seemed deserted and sad in the steady drizzle. But the local ristorante was busy enough, and served a delicious tortelli with spinach and pumpkin – and by the time we had finished lunch the sun was shining.

Next stop, across the Ceno river, the stream shrunk to a quarter of its winter width, was the tiny hamlet of Specchio, perched atop a steep hill with magnificent views of sunny valleys and rocky hillsides in all directions. I knew that my father had stayed in the barn of a “large, prosperous-looking house with an archway leading to a paved courtyard”: and there it was, unmistakeable and unchanged in seventy four years (to the very day). He had met up with PoW friends that evening, and all the local girls had come to see the “prigionieri Inglesi”: there had been quite a party, and afterwards the girls, on their way home, paused to sing an Ave Maria at the nearby shrine. The shrine is still there, a few yards from the ancient barn door.

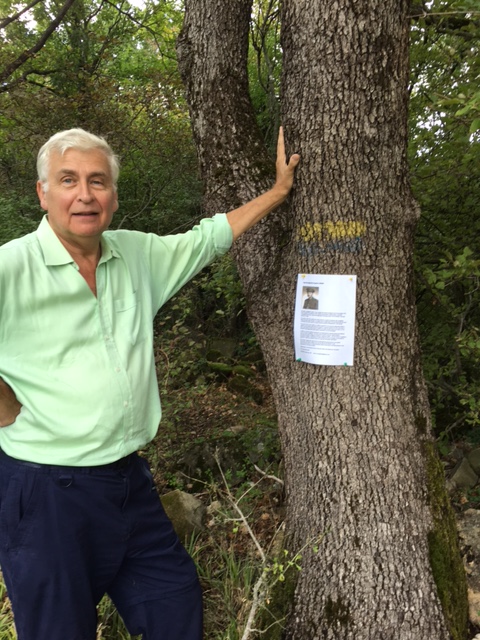

Three miles down a largely unmetalled road was Castelcorniglio, an imposing and now decaying residence gazing imperiously across a wooded valley. After a night sleeping rough in the woods because there were German soldiers about, Dad found a good billet in a nearby farm: he had his trousers repaired, and was given an Italian lesson by the friendly farmer. Both farm and castle were inaccessible, but we nailed our “thank you” notice to a tree beside the road and drove on through another ten miles of rocky valleys bathed in bright autumn sunlight to Valmozzola.

Gasping for a cup of tea, we found a smoky cafe where two large and forbidding ladies filled a pot for us, gave us two enormous hunks of lemon to go with it – and then delightedly agreed to pin up our notice beside a picture commemorating the brave men of the local partisan brigade.

DAY THREE

A long day today – eight hours of virtually solid driving, followed by a two-hour dash back to Fontanellato for dinner with our friend Francesco Trivelloni, the Mayor.

Sounds awful? Well, it was anything but! For the entire day, we were in the middle of the most jaw-droppingly beautiful Alpine scenery, with barely another car in sight – the Alpe de Succiso.

My father, impatient with their slow progress and a sense that his fellow escaper was in favour of stooging about for a while longer in the hope that help would arrive from the south, forced a decisive push south and reported to his diary: “Great day this! Have at last got us moving south and today we made good progress.” Ten miles a day at least of steep climbs and descents.

Corniglio had the smug air of a ski resort contemplating a busy season ahead, the locals basking in hot midday sun in the main square. Montebello, tucked away up a narrow valley, reminded my father of Clovelly, its seven houses nestling beneath a sudden tall rock crested by the superior eighth. He was here in a terrific thunderstorm and a mother suckled her frightened child throughout. Miscoso, deserted at three in the afternoon, burst into life in the local cafe, as lunch merged with tea and on into supper.

Last and best of all, Valbona tantalised us for two hours with misleading signposts, roads ending in tracks, new roads not yet on the map, and just the wonder of stupendous views and magnificent isolation. But we found it in the end, thanks to Heli’s ultimately victorious struggle with a recalcitrant satnav, nestling down down down in a deep dell, a single stumpy tower poised above a hugger-mugger of simple cottages and small barns.

As we pinned our “thank you” notice to the door of the Tower and headed north, we tried to imagine it in the rain – as my father had seen it. He met a chatty Italian Army deserter here, who offered to show them a good route the following day – only to run off before dawn with Dad’s precious penknife and their hostess’s best boots!

DAY FOUR

We had to miss out Casalino last night as it was getting dark and the route into the village looked difficult. This morning, befuddled as we were by last night’s donkey meat tortelli and thick red “frizzante” wine, we were defeated again by miles of brand new road tunnels, shown on neither map nor satnav. So we started in tiny Cervarolo, a cluster of stone-built cottages crammed at the end of a narrow track.

It felt so still and silent…then we saw it, the memorial on a wall listing the twenty-four men of this minute community, murdered by “infami Nazi-fascisti” on 20 March 1944. The oldest was 76, the youngest just 17. Nearby, a small stone byre had been converted into a shrine to the men, in an eternal salute to peace (“in sempiterno augurio di pace”), to the sons and daughters of Cervarolo, whose defenceless fathers (“inermi padri”) had been slaughtered. The shrine had been paid for by a Berlin theatre company in 1987.

It was hard to leave Cervarolo. Dad was tired when he arrived there, on 3 October 1943, after a twelve mile hike up and down four intervening valleys and around three 5,000 foot peaks. Somebody in Cervarolo that night gave him a good meal, a bed, and a haircut. We prayed that whoever it was had not paid with his life, six months later, for supporting the Allied cause.

After the deep sadness of Cervarolo, Gazzano, the next village came as a bit of a shock. Sprawling and prosperous around a boating and swimming lake, it baked in the midday sunshine. Dad slept here in a barn with a Frenchman, a Russian and a South African. We ate our picnic quietly and decided to go for a bit of a walk.

All over Italy, the national web of recognised walking tracks and ancient cartways is denoted with a red and white stripe of paint, slashed on any handy tree or pole. These paths cut right across the twists and turns of the highway, following a crow’s flight path straight from one village to the next, the steepness of the path mattering little to strong and wiry contadini legs.

We struck out on one such path, and after a while found a finger post pointing in the direction of Cervarolo. We stopped, thunderstruck: this must have been the very path trodden by Dad and Reg Dickinson 74 years ago!

The next two villages, Sasso Tignoso and Sassostorno, were both perched up steep mountainsides, well above the tree line. The first seemed to consist only of a tiny chapel; the latter (where Dad had an uncomfortably close encounter with a German staff car) was on the wrong side of a small landslide and several heaps of rock!

Vesale was like a small Austrian skiing village, with a glorious church on a rock, pretty-patterned paving stones, and the Alpine-chalet styled Locanda Zita in a little square. We passed our “thank you’”notice across the counter (trying to forget our son!s comment that it looks rather like a “Wanted” poster!) and immediately became the centre of attention for some minutes as staff, relatives and friends were all summoned to gaze at it in wonder and ply us with a barrage of completely incomprehensible questions!

Somehow we tore ourselves away, despite urgent requests to stay for drinks, dinner, the night and probably several weeks thereafter, and set off for our final stop in the gathering gloom: Montespecchio, on a hill in the middle of a wide bowl encircled by mountains. Dad was here during several days of torrential rain, but enjoyed the luxury of a new-laid egg for breakfast, and managed to blag a map off a friendly member of the local Caribinieri. He even had his boots repaired.

We had no time for such pleasures, and set off for the long drive back to our next base, Bologna.

Day 5

After four days of driving around ten hours each day, we gave ourselves a break in the raffishly cultivated city of Bologna yesterday. “Hic Manebimus Optime” is the entirely apt motto of our hotel!

Strolling through the city’s shady arcades, we came upon a wonderful exhibition of photographs of the Beatles in their early Hamburg days, taken by the German photographer Astrid Kirchherr. Love me Do and Yesterday played in the background and we were transported back to happy times. Lunch and local wine helped the fortifying process and today we were back on the road, heading south to Pieve di Cassio, a small church with three derelict hovels huddled around it. “A very poor billet” was Dad’s comment, and we had to agree.

Nearby was the Verzuno Bridge over the River Reno. We stopped at a small “Alimentari” to buy some local cheese and prosciutto for our picnic. The charmingly voluble Luana, whose shop it was, pounced on our “thank you” notice with gusto, and was soon regaling what quickly became a shop-full of lunchtime customers with her version of Dad’s story.

Tearing ourselves away, we climbed the hill to the village proper, arranged prettily around a cypress -fringed, recently-ploughed field, and soon had more company. First Giorgio, the very picture of an elderly contadino in his three-wheel mechanised cart; then Armando, in front of whose barn we were sitting. He seized unshakeably on the idea that we were German, and rushed off to fetch Gloria who was married to one. Luckily, she spoke good English, so we were able to sort out the muddle, and then had a lovely time with her and her partner Michael, a furniture restorer from Munich, putting the world to rights.

Like so many of the villages we have visited, Verzuno appeared prosperous, with smart-looking houses and well-tended gardens. In reality, what this means is that the self-reliant subsistence contadino lifestyle has all but disappeared, and been replaced mostly by weekenders with money from the cities, or holiday cottages.

On the way to Montefredente, in torrential rain, Dad had to cross a main north/south trunk road and railway line between Bologna and Florence – “one of our hardest obstacles” was his comment. By early October in 1943, the Germans were rushing thousands of troops south by road and rail and, in this very area, constructing the Gothic Line, one of several east/west defensive positions against the anticipated eventual Allied advance north. By this time, too, notices had been posted in every village, threatening imprisonment, or worse, for assisting Allied escapers.

Dad and Reg Dickinson had tea in Montefredente (now rather suburban and plain) with some refugees from Bologna, presumably fleeing the Allied bombing – or possibly Jews, fearful of the occupying Germans – but it was another damp and unsatisfactory billet. They were relieved though the next day, their first in Tuscany, when they got to Peglio, 3,000 feet up and very chilly, to find “an excellent billet, and roasted chestnuts around the fire after supper”.

On our own way to Peglio, we passed a museum dedicated to the Gothic Line, shut for the day but hosting in the garden an array of field guns and mortars, a tangle of barbed-wire and some authentic-looking notices announcing “Road Mined” or “Heavy Guns Firing Across Road”.

Just down the road though was a far more potent reminder – the sombre Futa Pass German War Cemetery, with over 30,800 simple grave markers, many bearing only the legend “Ein Unbekannter Deutscher Solda”’.

We raced back along the motorway to Bologna.

Day 6

We started the day in a small town called Marzabotto, a few miles south of Bologna, where 770 local people from villages all around were massacred by the SS in October 1944 – punishment for local support for the Partisans. The victims, whose ages ranged from a few days old to over 80, have no graves as their bodies were thrown into a pit and then blown up. In a modern crypt under the local church, there is however a carved memorial stone for each victim; outside, there are haunting photographs of those who died, and messages from the scenes of other mass killings from around the world.

As we drove thoughtfully away, it started to rain – thorough, wetting autumn rain of the kind endured, for days on end, by my father and many of the other escapers back in 1943. The temperature dropped by several degrees, thunder rumbled and lightning crashed across the sky.

Just as my father had done on 14th October 1943, we crept along mountain roads and rocky canyons now awash with water teeming from the hillsides, and found our way eventually up a winding narrow track to Mantigno. If ever there was a model for Cold Comfort Farm, this was it! A farmer loading logs onto a tractor in a yard crammed with rusty equipment ignored us in a determined sort of way, so we contented ourselves with a desultory poke about in the mist and rain, pinned Dad’s picture and the thank you note onto the door of the abandoned church – and fled.

Our next stop, again at the end of a long and winding road up through dripping pines and hanging grey cloud – “a difficult route again: mountains very steep”, as my father commented in his scribbled diary) – was Albero, about thirty miles from Mantigno by road, perhaps half that by mountain track. This time the road was newly surfaced with smooth, black tarmac, so we were looking forward to a warmer welcome of some kind. But no, we found ourselves in a stone Marie Celeste, a grim huddle of grey houses brooding at the far end of a driveway marked “Privato”’ in rather large and emphatic letters.

We ventured forwards, poised for retreat, furtively pinned our notice to the door of the former church, now clearly used as a barn, and beat a hasty retreat before the hounds were set on us. This slightly unsettling episode gave us some insight into just how it must have been for the escapers as they approached some forlorn farmhouse at the end of a long and damp day of tramping in the mountains – cold, hungry and afraid, with little to look forward to apart from, at best, a damp barn and some poor scraps to eat. As it happens, Albero was kinder, thank goodness, to Dad than it was to us, as he found a “Good billet. Chicken broth.”

With some relief, we headed off for San Benedetto in Alpe, our last stop on this first stage of the journey along my father’s escape route. The village is a prosperous Alpine resort, still notably silent and apparently deserted on this wet Sunday afternoon, but much more settled and comfortable than our two earlier halts.

On the way to San Benedetto, Dad and Reg Dickinson ran into a group of Partisans, and were invited back to their hideout for the night. Here they met up with a chipper New Zealander called Charlie Gatenby, who had managed to escape from Modena Camp after it had been overrun by the Germans, hidden in a rubbish cart. Looking and smelling like a particularly disreputable tramp, he had ambled south on his own and been taken in by the Partisans a night or two previously. They had regaled him with copious draughts of rough local wine, and tales of their murderous attacks on Fascist neighbours – and were very keen that all three soldier escapers should join their group.

Dad liked Charlie immediately: “We now have a New Zealander travelling with us. He is good. Poor billet.” Although he didn’t know it at the time, the meeting was to change the course of events for him dramatically.

And that’s all for now!! Thank you so much for reading this Blog. Heli and I are off home now, but we will be resuming the Blog on 16th October, for the next stage of my father’s amazing journey and we do hope you will join us for the next instalment then.